photographs and interviews by Chris Ortiz

originally published on chris-ortiz.com

There I was: deep in the heart of unknown territory, surrounded by unknown foes, ready to slash and die. My head is on a swivel, eyes darting back and forth, I was ready to spring into action — to defend my honor, or my life. The cute redhead I had as a date that night leaned over and said: “Is something wrong?”

“I’m not sure.” I replied. “I don’t feel right — like something is off.” She looked at me, shook her head, pinched up her lip, cocked her brow, and said something to the tune of “Just relax. It’s cool.”

It’s cool. Yeah, it’s cool. Then it hit me, like a tons of fat-kid, stage-divin’ ass, it hit me. “It’s too fuckin safe.”

I was in Nashville, and it was 2014. I didn’t know the no-name band at the local punk rock show, but I had seen them 1000 times in other cities and other times. I was far from my home punk scene of Lawrence Kansas. Even though The Outhouse is long gone, and some of my favorite local bands are defunct, I still have a healthy respect for my scene because it will set your ass straight when it needs to.

Back in Nashville my date turns to me and says: “Are you gonna make it?”

“Yes” I said. “It’s just… It’s just I don’t feel like I’m gonna get stabbed or nothing.”

“Umm? Ok.” Is all she said.

“It’s too safe. I don’t feel any energy in the room. Nobody is into it.”

Punk Rock has become safe, and I fuckin hate it. See, I’m from a scene that was dangerous. Punk Rock, to me, should be dangerous. It should be dangerous to me, to you, and to the sleeping giants of society that won’t see the revolution coming. Punk Rock should feel like you might get stabbed in the bathroom. You might have to boot-party a Nazi to round out the night. It means vomit in your car, and sticky shit on your boots. It was visceral and greasy. There was not a god damned thing safe about it, except for your friends. But even some of those rat-bastards would steal your mom’s credit card, and bang your sister. Back in the day my scene was known for bands that were notorious for doing unspeakable things to farm animals on stage. Hell, one front man used to cram marshmallows up his butt. Bands were in your face, and dangerous — bands like Kill Whitey, Cocknoose, Filthy Jim, Mopar Funeral, and The Unknown Stuntman. God forbid that one night would go by without some dipshit getting his head kicked in for whatever reason we could think of at the moment. It was awesome. I remember tripping at shows, and having a religious experience in a corn field while D.I. or Toxic Reasons blared as the twisted soundtrack. It was an angry teen’s Valhalla. It was sheer bliss, and Anarchy, and unabashed freedom.

Back then you had to prove it. When rednecks and cops came calling, you stood and fought them. When you caught the jocks and bullies from school in your world, you taught them a lesson. Frat boys be damned.

But now it’s safe. Punk Rock should never be safe. Punks were meant to destroy. Now teachers and moms have blue hair, and its kitschy. People with corporate jobs have tattoos and piercings, and no one bats an eye. Somewhere, there are real punks left. Street level. In a part of town where your blue haired mom won’t go. Somewhere, there are loud guitars and blood and beer on the floor. There is a kid writhing on a makeshift stage, screaming shitty poetry over feedback and dull drums. There are scars, and drugs, and fear.

If you listen to corporate “punk,” if you have blue hair and Hot Topic jewelry, and have never been punched in the mouth by a skinhead — or better yet punched one yourself — you are not a punk. You are bullshit. Live a little. Start your revolution. Tear it all down. Safety is for the weak. If there isn’t blood on you or the band, it was a shitty show. Pick up a guitar. Scream to the world. Safety is for complacent pigs. Stand up for your freedom. Wanna be a punk? Bleed for it. Show me the scars. Freedom isn’t free.

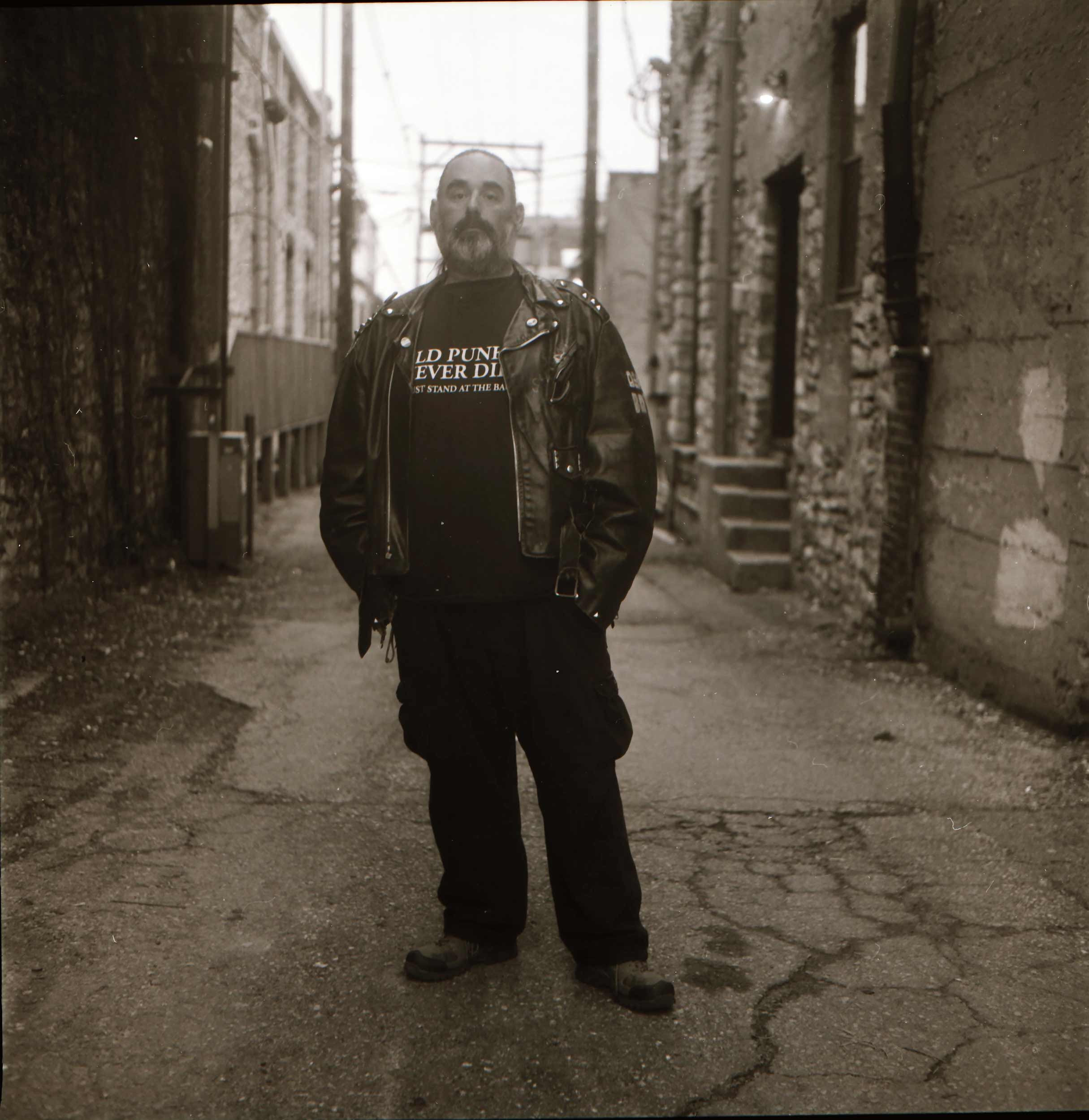

Punk Rock has become safe, and I fuckin hate it. See I’m from a scene that was dangerous. Punk Rock to me should be dangerous

— Shane Thirteen

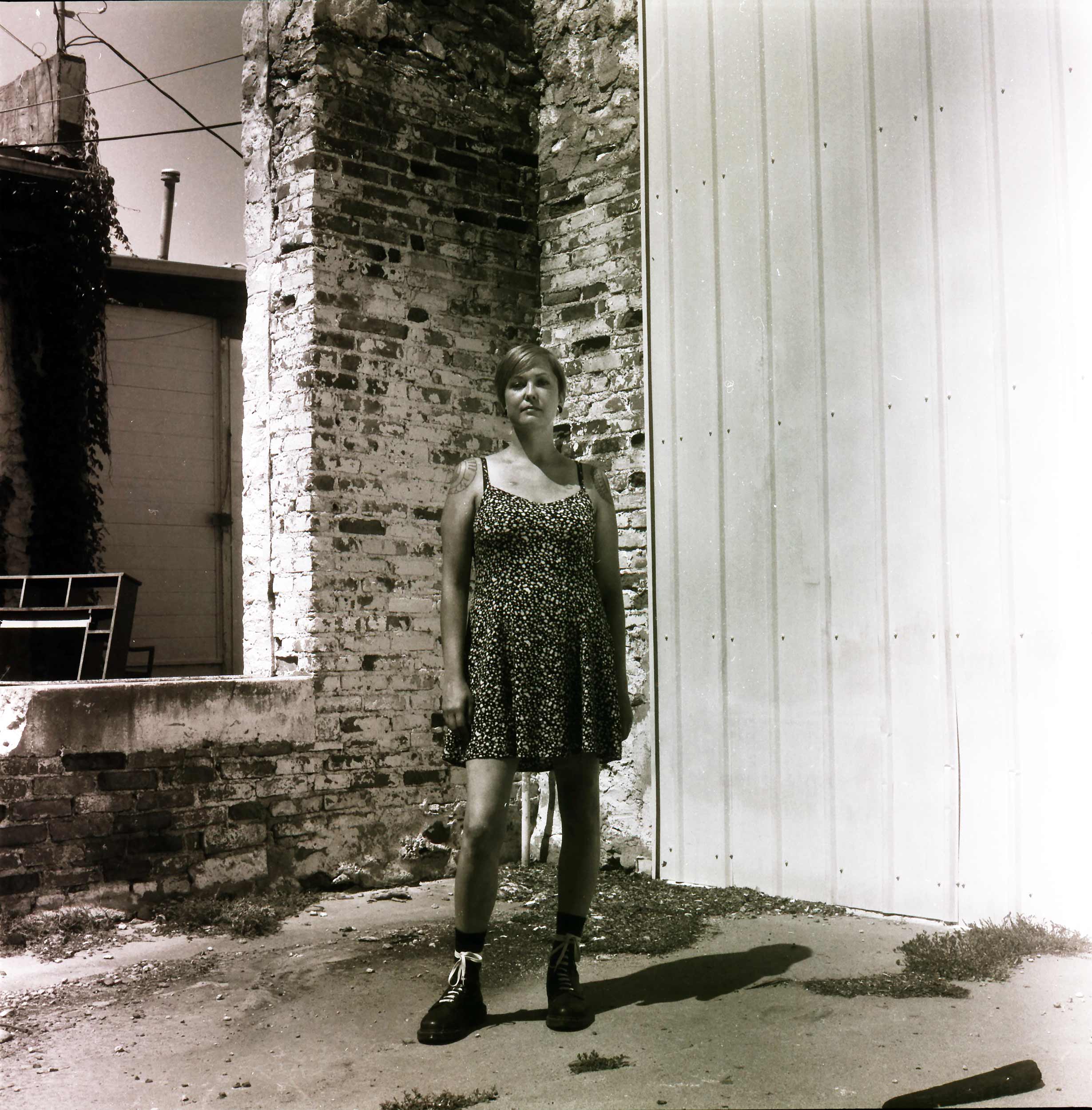

I got out of a bad marriage 6 months ago. He hated live music, and he was very controlling — which is why I went from seeing two or three shows a week to nothing for about seven years. I was diagnosed with lymphoma nine years ago when I was 23. The scars on my neck are from all of the biopsies. The scars on my chest are from the three power ports I’ve had implanted over the years for chemo, etc. I’m a chronic relapser, so it never truly goes away. But I’m going on three years in remission now, and being so close to death for so long has given me a weird way of seeing life. I don’t give a fuck what people think, especially when they stare at my scars.

Life is too short to care about that sort of thing, so I refuse to cover them up. I used to be into punk music in high school, but I lost touch when I broke up with the punker dude I was dating. I needed some guidance. So when Josh and I started hanging out, he would give me his iPod to take to work. I went hog-wild — I loved it all. I love the energy. I love the attitude. I love the loudness. I love how unapologetically opinionated and political it is. But most of all, I love what punk music is about: it’s about connection, and acceptance.

Ever since I can remember, I always wanted to wear combat boots and floral dresses. It’s super 90s, I know, but I didn’t really have the confidence until I was in my mid-20s. Now it’s what I wear most of the time.

[The cancer is] Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. I ignored all the symptoms and kept partying. A huge tumor popped under my clavicle, and I only noticed it when I got syrup on it while I was working as a barista. I was stage 4 by the time I started chemo for the first time. That means that the tumors were everywhere — above and below the diaphragm — and that I was symptomatic in every way. Each treatment works, just not for long. Sometimes I get 6 months. Sometimes I get years. The side effects from the treatments stay with me: new problems. But I’m alive. Each day that I wake up is a good day.

I’m going on 3 years in remission now, and being so close to death for so long has given me a weird way of seeing life. I don’t give a fuck what people think, especially when they stare at my scars.

— Sara

What was it like being a minority in the scene? I rarely look back to the past since I’m so pumped for my future. A lot of my friends can look back on the skinhead scene fondly. I can find some love in the experiences and friendships I made too, but I feel remorse for things I’ve said and done.

I didn’t come from a scene where I felt like a minority. I was a poor kid like everyone else. I grew up in the San Antonio scene. It is mostly made up of Latino skins, punks, hardcore kids, rude boys, etc. I didn’t see many white faces at shows that didn’t belong to touring bands. Maybe I just didn’t associate with white kids because they weren’t from my part of town, or because they didn’t dress like me. Most of the fighting in the scene had more to do with which crew you ran with, rather than racial beefs. It threw me for a loop to hear from the media that we are all a bunch of racist assholes.

It wasn’t until I moved to Oklahoma City in the late 90’s that I began to feel like a minority. It’s no secret OKC had Nazi elements in its scene, but I wasn’t treated terribly. It was hard to wrap my mind around it.

My patriotism amped up to nationalism after 9-11. I started having long political discussions with other skins in other towns, and began listening to Rock Against Communism. I’ve always laughed at the idea of people living their lives by band lyrics, but it really made me want to push the envelope. I was furious with anyone I considered to be liberal. Music has power, and I truly believe that listening to angry shit all the time will let the anger seep in.

I became obsessed with militia groups like The Minutemen Project. But when I approached them at an anti-immigration rally with one of my white friends, they wouldn’t even look me in the eye. They gave her literature, and she threw it away. This set off a time of self-reflection, and a shift in politics. I was used to hearing things like “Aaron’s one of the good ones” but it made me wonder if I was just someone’s token minority.

I converted to Christianity. And the birth of my niece made me think about the legacy I would be leaving. It’s funny — most Christians align themselves with the Republican party, but after giving my life to Jesus I found myself having more compassion for my neighbors, and adopting politics that might be considered more liberal. I started cutting people into the scene who weren’t deemed worthy by my peers. It started a rift. A girl broke my heart shortly afterwards, and I was also difficult to be around. I lost some longtime friends. I started questioning everything. You find out really quick who your true friends are when you are deep in the gutter of life.

I decided that I should reevaluate my life, and I started going to school. I’ve always loved education, but I never thought I could manage the money to go, and I also thought that universities were rich, liberal cesspools. My ideas on that have changed somewhat. If there’s anything that’ll make you rethink your politics, it’s being surrounded by the people you may not have liked in the past. It’s easy to hate someone when you don’t know them face to face. I have spent time with people of different races, religions, sexual orientations, political affiliations, etc. I sat next to an Iraqi in history class, and we traded notes on what he was taught, and what I was taught. The best place for open dialogue is an educational environment, or the military.

I’ve learned to embrace myself, my Latino culture, and the moments that have shaped me. And I’ve allowed myself to dream. I don’t just focus on the “America” I want based on the politics of a scene. I’m a better citizen now. I contribute to my community through service work.

Although I’m nearing 40, I will always have a love for the music, and for the skinhead subculture. I can see why the scene draws people in, and I hope that others find the same sense of pride that I learned from it. Pride in who you are. Pride in working hard for what you have. Pride in not taking no shit from people, and always standing by your guns.

I sat next to an Iraqi in history class, and we traded notes on what he was taught and what I was taught. The best place for open dialogue is an educational environment, or the military.

— Aaron C.

I moved out during my senior year of high school. At that point I wasn’t really hanging out with friends, and I hadn’t been to many shows. I think the first one was The Dead Milkmen; we snuck in. I was living with some guys in their darkroom, and I paid rent by cleaning their house. I don’t think I did such a great job. Some of these guys were involved with KJHK, the local radio station, and they were friends with a lot of bands. So there were always parties at our place; always a show to see. I met a lot of punk kids.

I eventually moved in with a friend from school. We sorta had an open house policy, I guess. Pretty much anyone could crash there if they needed to — the windows were always unlocked, and kids could crawl in. We left mattresses on the floor. We would hang out on porches, drink thunderbird and whiskey, talk, take pictures, and do each other’s hair.

But The Outhouse was where we really wanted to be. We’d get dressed up, pile into someone’s car with some drinks and head east on 15th until we saw that cornfield. We’d get there before the bands started, and be there all night. I saw some amazing shows. That was a great time for me.

I remember one time when a few of us decided to go to Hutchinson, Kansas because my friend said he knew a girl that we could stay with for a while. So we piled onto the back of a truck, in the winter, and drove there. It was stupid cold. We huddled under blankets and tarps, but there was ice everywhere, and it was miserable. When we finally get there, it turns out that it’s the wrong house. But the people still let us in — even though we looked crazy with our torn up clothes and bright hair. They let us stay for a while, until we found somewhere else crash. We were there for a week or so, all crammed in a tiny place, sleeping on the floor, and eating ramen.

I love art. I love creating art. Whether it’s an actual piece to display, or bright hair, or torn up clothing, I think the scene at the time really fed my desire to be creative in every way. The music, the people, the friendships, the wild craziness of that time was important to me, and it allowed me to feel comfortable with the way I saw myself.

But I guess I sort of backed away from everything once I became pregnant with my daughter. I really focused on getting myself together, and making sure that I was in a better place for her. But I did maintain a few of those friendships. Several of the people I liked the most have died — some moved away. But those few years that I was immersed in that little “scene” really made an impact on my life. It helped me realize that it was ok to just let myself shine the way I wanted to. I have so many great memories: the people, the late night conversations, the dumpster diving, the hair dye disasters, the parties, the bands, the fights, and the laughter.

I wouldn’t trade those years for anything.

But I guess I sort of backed away from everything once I became pregnant with my daughter. I really focused on getting myself together, and making sure that I was in a better place for her. But I did maintain a few of those friendships.

— Rachal

My friends and I decided to leave Dallas in 1996. It was my on-and-off homeless home at the time. And we loved it there — mostly because it wasn’t Oklahoma. But it was time to move on.

We had to split up because hitching rides as a group of five was too hard. So half of us went with the alpha male, and the rest went with the beta. Of course I traveled with the “betas.” In all fairness, I was not an alpha. I was a closeted trans woman in a homeless crust-punk suit.

I wasn’t allowed to sleep on anyone’s couches in Lawrence anymore, so I started sleeping in a shed that was in front of a gas station. I’d pass out listening to Tom Waits or The Pogues on a walkman. I guess this was just me being macho. But the shed was way too cold come November, so I ended up sleeping under the bridge with about eight or nine friends. We had two fires going, and all of our perishables sat outside. Everyone had food stamps. It was so cold that we didn’t have to worry about it going bad.

We were down there for about a month before everybody trickled out of Lawrence, leaving just my friend and I. Then we finally decided to go too. I must have found a floor to sleep on or something. That time was a pretty big blur for me; the only way to deal with the horror of waking up at four in the morning in twenty degree weather was to drink yourself completely numb.

Christina and I were downtown the day after we moved out. A police officer asked us to identify the man who had hung himself right there under the bridge where we slept, where we lived. He must have killed himself the day we left. We didn’t recognize his clothes in the pictures. He wasn’t a punk — just an older homeless man. We hoped that somebody would know who he was.

I felt like I was invisible. I hopped trains. I hitchhiked. I was hospitalized because of alcohol-involved accidents. Punk was always a way to make friends with people who I thought shared the same interests. But that dissolved around me. It was a bunch of broken men, mostly, telling racist jokes around a campfire, drinking too much, and hazing the weaker elements of the group. It was a very dirty frat. It took a few years, but I finally got over the mystique of being a homeless squatter punk. It was going to kill me. It tried more than once.

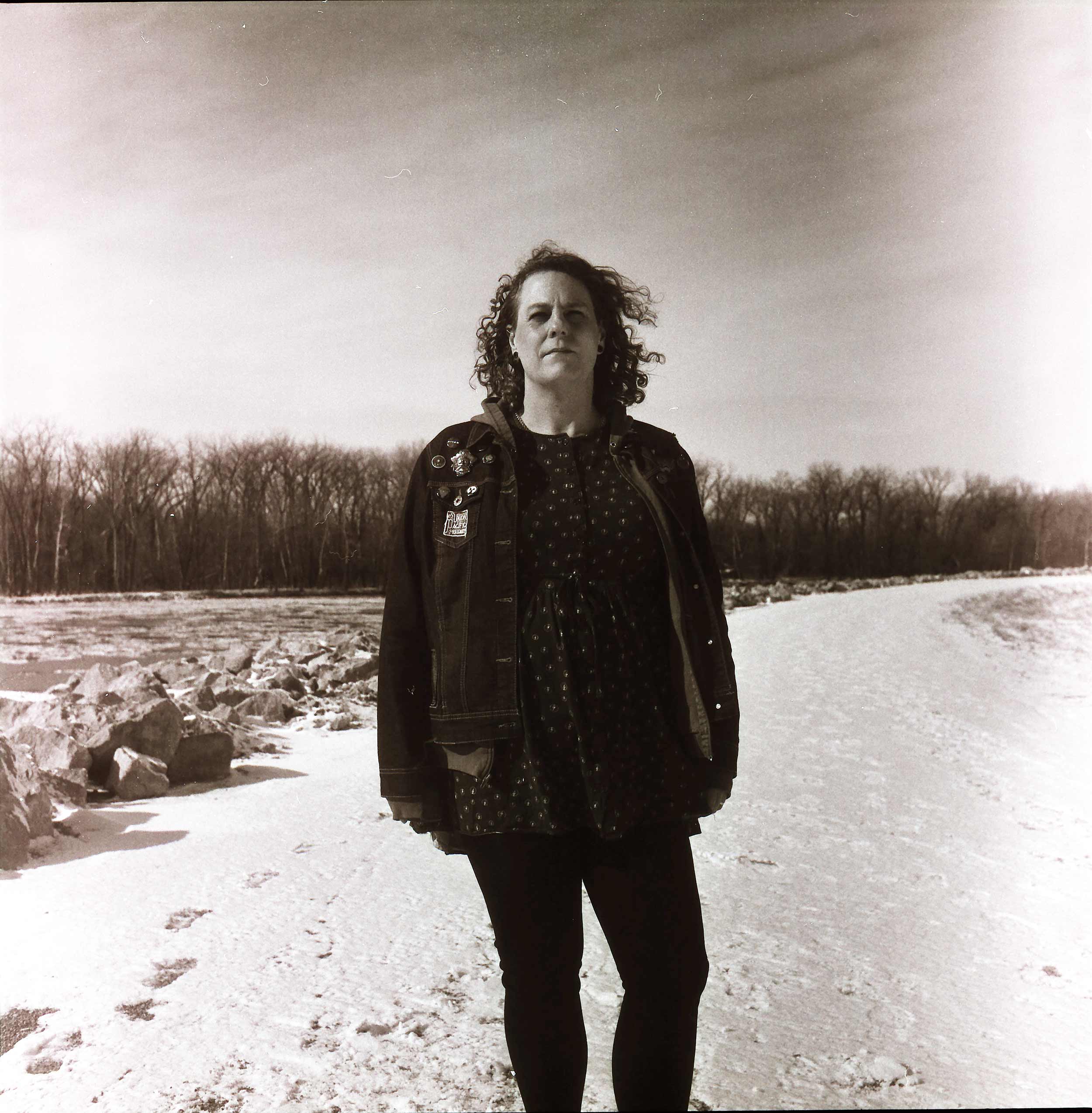

I fell in love when I was 25. I got my first job, and started over. By 30 I was telling everyone that I was going to transition from perceived male to female. That went over like a lead balloon. If quitting drinking made me feel isolated, transitioning made it worse. I was ostracized by most of my peers, but it was fine. For the first time, I finally knew who I was.

I’m in a much warmer place now. My gender markers are fixed. I live in a historic city, where I can accomplish much good by showing young trans kids that they too can find the courage to make the change. Punk is dumb, punk is dirty, but punk also makes you strong. And the marginalized people of the world need strength — now more than ever.

I fell in love when I was 25. I got my first job, and started over. By 30 I was telling everyone that I was going to transition from perceived male to female. That went over like a lead balloon. If quitting drinking made me feel isolated, transitioning made it worse. I was ostracized by most of my peers, but it was fine. For the first time, I finally knew who I was.

— Christi

I found the punk scene at a young age — something like 13 or 14 years old. It was around the same time that Green Day’s Dookie or Rancid’s …And Out Came the Wolves albums dropped. It was an eye-opening experience, to say the least. Before that, I listened strictly to Alternative Rock: albums like No Need to Argue by The Cranberries, and if you go back further, you’ll find an odd mix of Country and bad 1980s pop. But something clicked in my head when Welcome to Paradise and Time Bomb first hit my ears, and things really fell into place shortly after when I discovered Ska-core, the devil and more by the Mighty Mighty Bosstones. The music inspired me, and it filled a void in my life. Its energy gave my teenage angst an outlet. It made me want to be creative. I was able to feel free and had the ability to channel my creativity into art and allowed my own depression to take a back seat in my mind

My lifelong venture in the world of photography started about eight years earlier, but it didn’t cross paths with punk rock until the late 1990s or early 2000s when I started spending most of my time at a crusty punk collective called “The Pirate House.”

This is where I started to photograph my friends during every day events, and at night during concerts. What I liked the most about them was the crust look — how they wore it with pride, and how there wasn’t a soul that could talk them out of it. It was who they were, and what they loved. It was a look that I had only seen a few times before, and my parents demanded that I stay away from them. They were “dirty,” or “scary.” In reality, my parents (like so many other people, even today) are scared of what they don’t know, or don’t understand.

My appearance changed. Patches of my favorite bands, and metal studs appeared on my clothes. My friends started to change too. The backbone that united us was the love of music, and the scene. If you see someone who looked similar to you randomly walking down the street, you can stop them to ask what they are into. It was often the beginnings of a friendship.

I was at the Pirate House pretty much every night. Sometimes it was a vegan potluck, and sometimes just spending the evening out on the porch with friends drinking cheap beer. But other times it was community outreach: stuff like volunteering at the local soup kitchens, or standing up for worker’s rights. Of course there were also plenty of house concerts. Independent bands like This Bike is a Pipe bomb, The Sissies, and The Short Bus Kids were the norm.

It was an education and a sense of a family that I didn’t get at home, or at school. It was completely welcoming and it did not discriminate. Your sex, race, or religion didn’t matter. Nobody cared if you were bald, or had dreadlocks to your ass; if you were fat, or skinny; if you had glasses, or not. I grew up in a divided household since I was 10 months old, and I was of half Latino and half European descent. I never felt like I fit in anywhere, but I did fit in here. And it was a good group of people. But it didn’t keep us from being judged for it.

We are All We Have Tonight is an ongoing 10-year project that covers how my scene has developed between the 40th year anniversary of the subculture’s birth and its upcoming 50th. It is a collection of images and stories from the members of a community. They hail from all walks of life. They have changed and stayed the same, just as the scene has changed and stayed the same. In either case, these people defy their stereotypes — they are not uneducated, drunk, drug-addicted trouble makers and bums. Some consider themselves activists, but most just call themselves decent human beings.

The people defy the stereotypes of uneducated drunk and drug addicted trouble makers or bums. Some also call them activists, but they just call themselves decent human beings.

— Christ Ortiz, Photographer