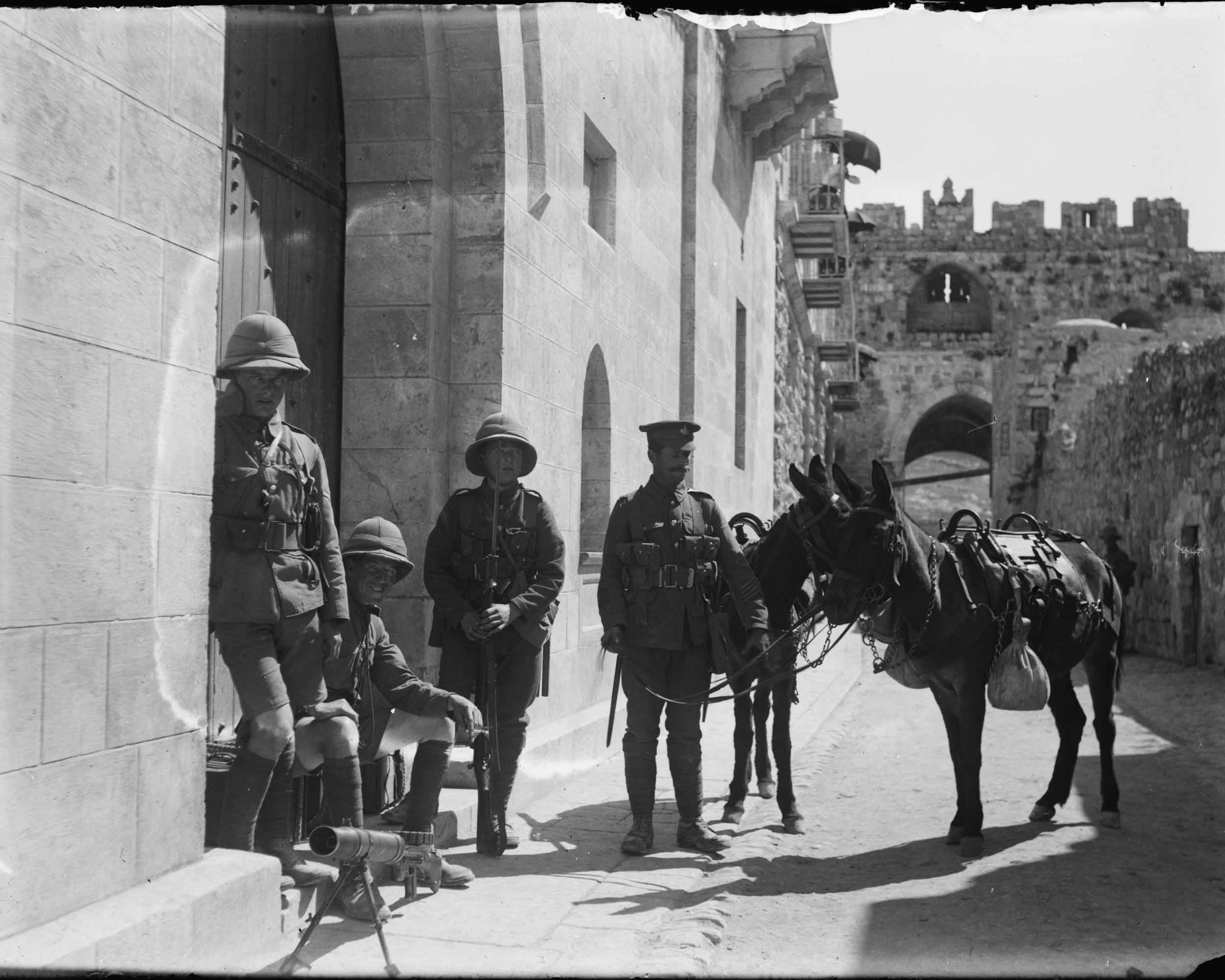

Like all cities, Jerusalem is built on its past, however unlike most cities, its past does not build its present structure only in a physical sense — rather Jerusalem is constantly shaped by the power of the legends and the hopes that billions have laid onto its narrow alleys, and dusty corners.

Small, ordinary places are imbued with cosmic significance, and as such they are often preserved from destruction, and also extensively documented throughout the ages in ways that far outstrip the forgotten corners of other historic cities.

This tendency presents a unique photographic opportunity. Jerusalem has always been high on the shotlist of pioneering photographers since the earliest days of practical photography in the mid 19th century. The wealth of images that exist from the 170 years since then, combined with the relatively unchanging face of the city’s landscape, means that one can directly compare images from today against photographs that were taken decades, even centuries ago.

Conveniently, the Library of Congress maintains an extensive archive of copyright free photography that goes back to the earliest days of the medium. A simple search for Jerusalem yields over 16,000 results. I spent a few hours sifting through these images to select those that were most interesting to me, and that were taken in readily identifiable locations. And then I spent a few days walking around Jerusalem’s Old City replicating the exact perspectives of the shots.

There is no particular order or focus to these pictures, as it is highly dependent on what is available in the public record. This is an ongoing project, and I plan to add more images to this photoessay as I discover new images to add.