Mount Gerizim—a stout, scraggy mountain that rises up to a height of about 900 meters in the heart of the West Bank—is another one of those places that seems to punch well above its weight. Much like all of the other famous mountains in the Holy Land, it would barely qualify as a foothill if it went up against an Alp or a Himalaya. It is unimpressive even in its own surroundings, with an undistinguished appearance and a peak that is only slightly higher than its neighbors’. But, much like all of the other famous mountains in the Holy Land, this unassuming hill is in fact the beating heart of an ancient religion. Overachieving topography is a common thing around here, where dusty landscapes and middling ruins have long been a perennial cause for competing passions and global attention.

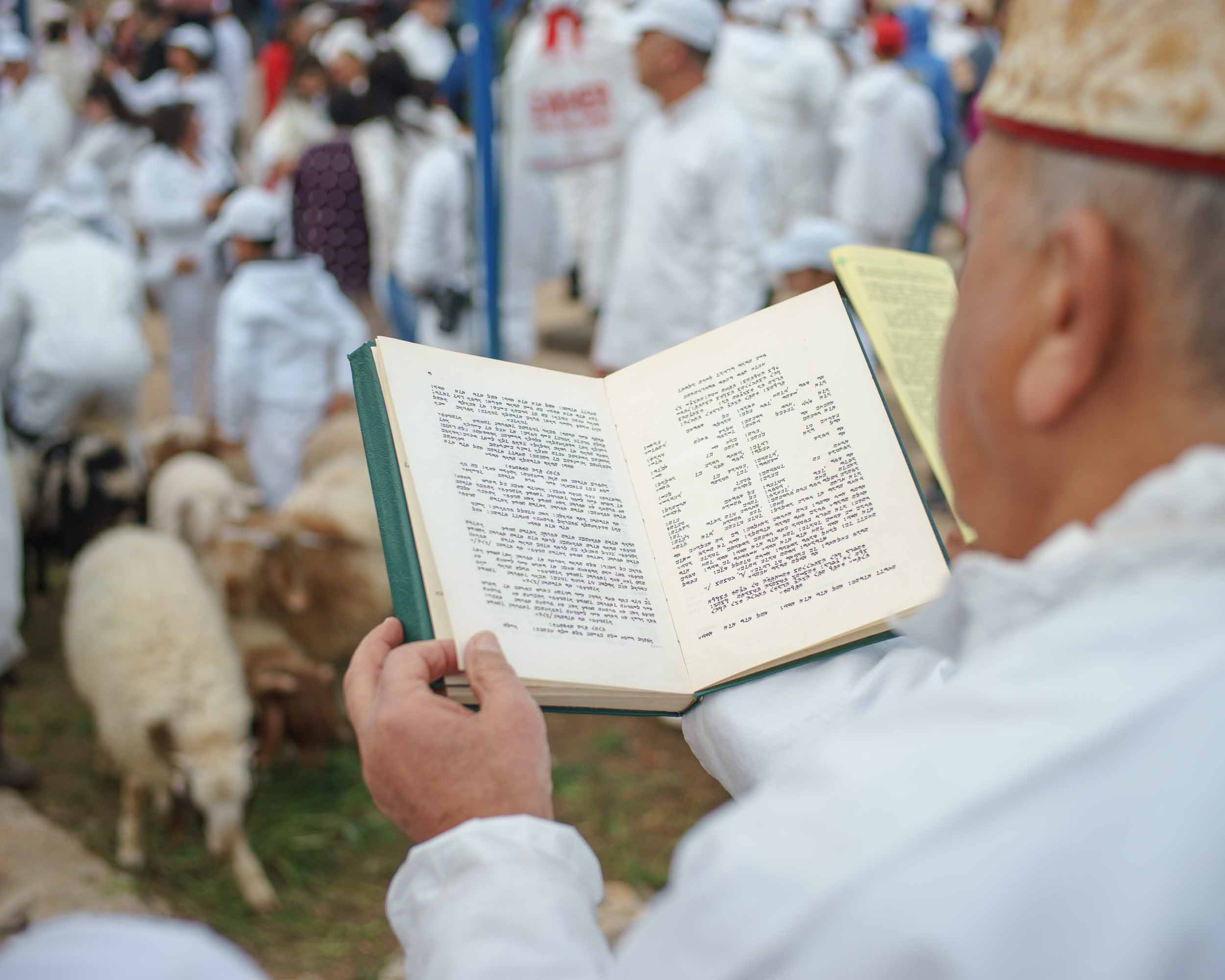

So every year, when thousands of spectators from around the world gather on the slopes of this nondescript mountain to observe the ritual sacrifice of a few dozen purified lambs, contradictions of scale are the norm. It is both exotic and ordinary. It is a public spectacle that attracts global attention, but its purpose is also deeply meaningful and private. There is much blood and death, but there is also a peacefulness to it. It only makes sense once you’ve really seen it.

There is a spectator area. The crowd quickly swells to press against the tall fences erected to keep the crowd out of the ceremonial compound, a paved yard about the size of two, maybe three, basketball courts. There is a sense of excitement hanging in the air, like everyone is waiting for a show to begin. I suppose they are. The bus-load of middle-aged Korean tourists was the first to arrive, claiming all the good seats in the bleachers (yes, bleachers), while kids climbed on nearby playgrounds and claimed the last remaining good spots. Everyone else strained on their toes to find a decent view in the thickening crowd. The ceremonial compound itself is technically closed off to outsiders, but you can easily get in if you ask nicely, point vaguely toward someone who looks like they belong inside, and tell the guards that “that guy over there said it was ok.” A handful of news crews, documentarians, and the odd Korean tourist with an overkill camera are milling around inside. The faint buzzing of consumer drones overhead marks this as a distinctly 21st-century spectacle.

But at the moment there isn’t all that much to see. On the inside of the barrier fence, the remaining members of one of the world’s more ancient religious sects mill about casually, seemingly oblivious to all of the attention directed at them. Some are wearing colorful robes, many are busy preparing the fire pits, while the boys are chasing after the sacrificial lambs, herding them into a corner—gleefully taking responsibility for the task of keeping them there. The kids, especially, they’re the only ones on the inside that seem to let on that they are excited. They tell me that this is their favorite day of the year. They tell me how many years they’ve been old enough to participate in the ceremony. They tell me that they think that the bloody ritual is cool. They tell me that they love being a part of something special. They also tell me that it is fun to see all their friends.